The site of Old Paphos is situated within the municipal boundaries of the modern village of Kouklia at the southwest coast of Cyprus. It became known as Palaepaphos, after the 4th century BC, when the kingdom's capital was shifted to Nea Paphos, some 15km to the west. Palaepaphos is an extensive archaeological landscape. In the Late Bronze Age, the site held the urban and administrative centre of the regional polity, and in the Iron Age it was the seat of the city-kingdom of Paphos.

With the aim of mapping the visible and no longer visible monuments of Palaepaphos, the University of Cyprus initiated fieldwork research in the area of Kouklia, in collaboration with the Institute for Mediterranean Studies of the Foundation of Research and Technology, Hellas (FORTH) and the Department of Lands and Surveys of the Republic of Cyprus. The programme achieved to accumulate a vast amount of archaeo-cultural information dispersed over almost 5 sq.km. The data were collected under a single digital roof, the "Archaeological Atlas of Palaepaphos". In 2003, the same team conducted geophysical surveys in selected sectors of the archaeo-environment within the Palaepaphos nucleus. The second phase of geophysical surveys was undertaken in 2007. During this phase, the survey team employed resistivity, magnetic and GPR techniques to scan 56,202 sq.m. within the area of Kouklia. A third small-scale geophysical survey was undertaken in 2010.

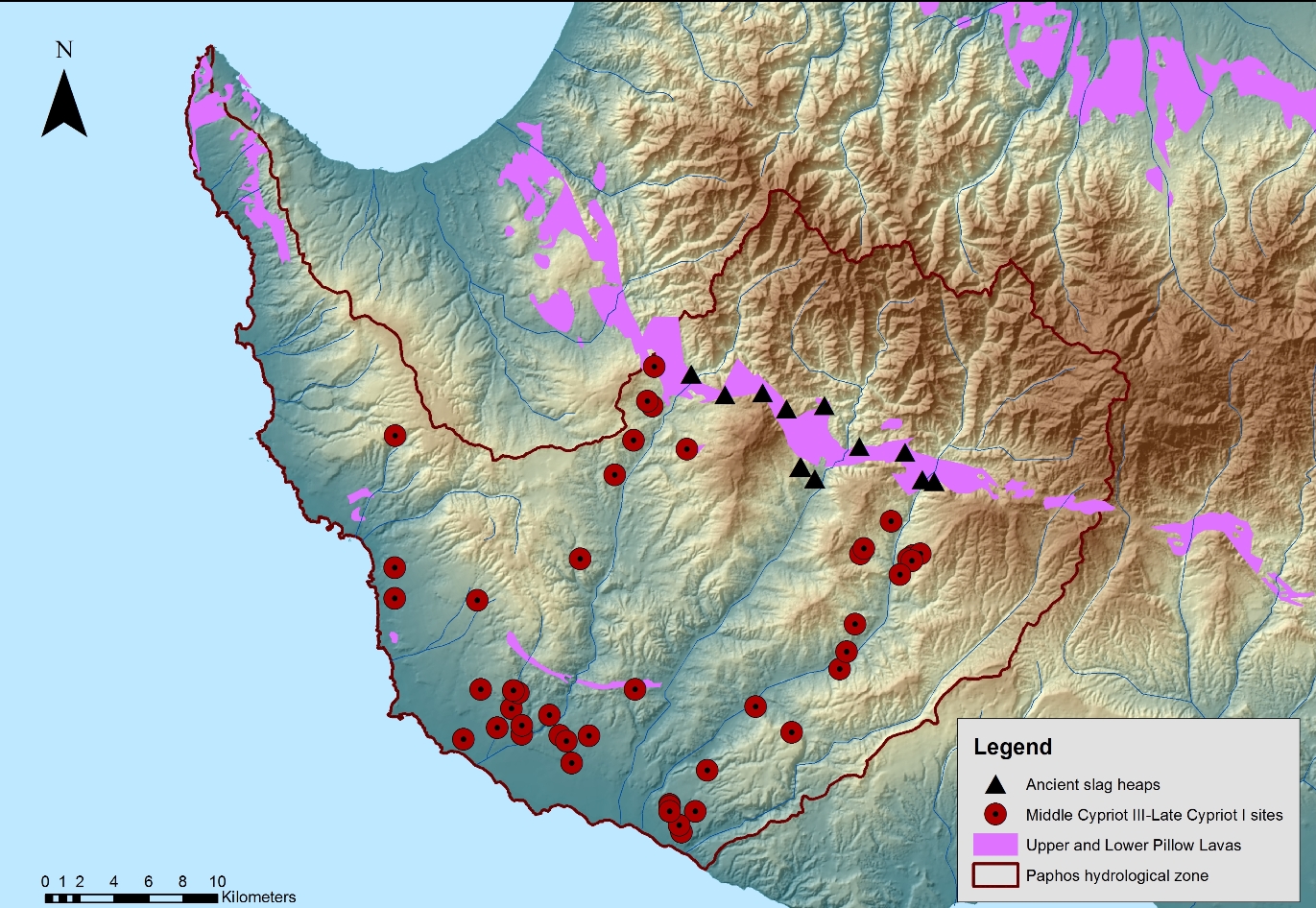

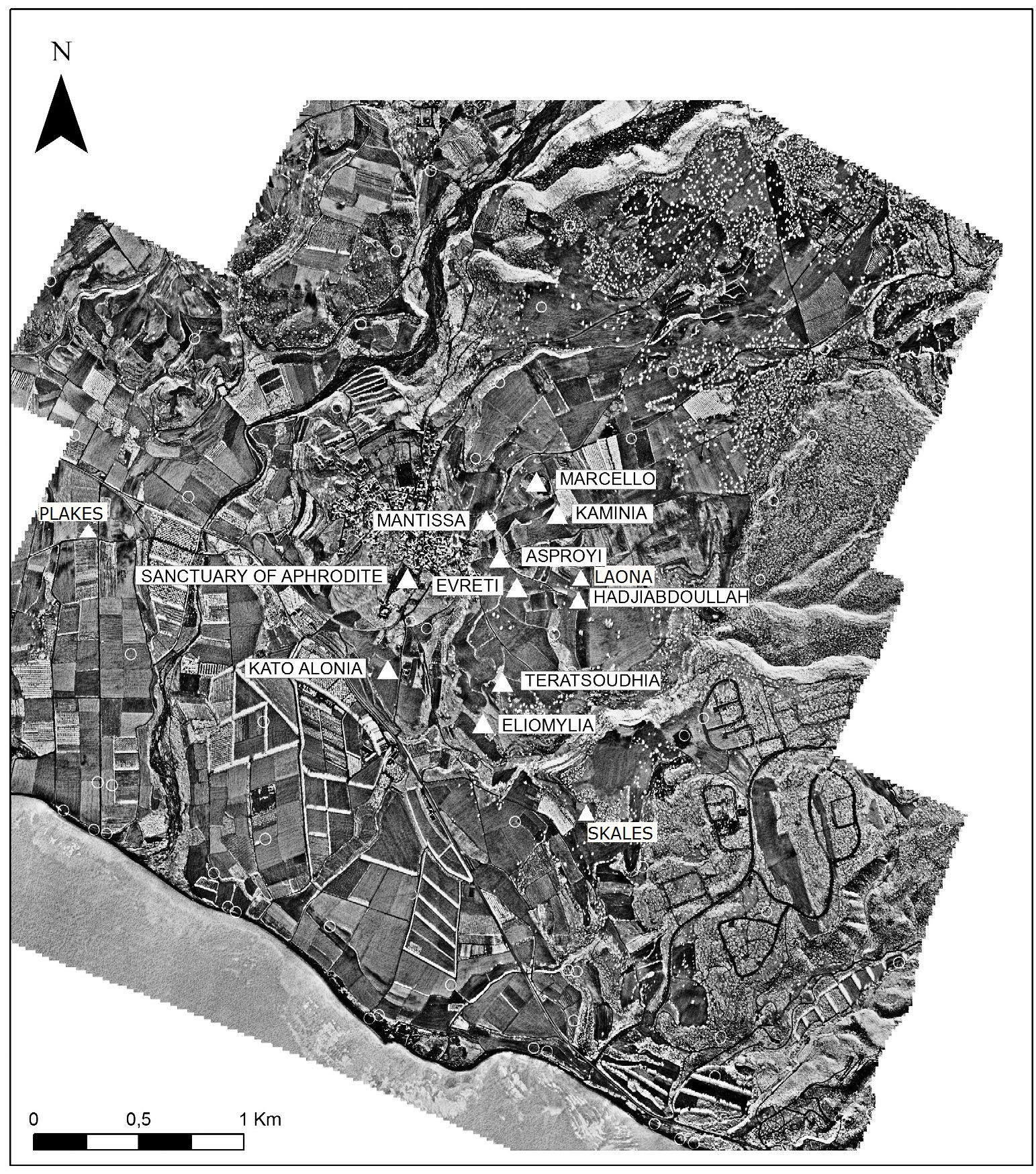

The University of Cyprus has been undertaking targeted excavations in the area of Palaepaphos, within the framework of two interlinked projects, both of which are directed by Professor Maria Iacovou. The first programme is entitled "A long-term response to the need to make modern development and the preservation of the archaeo-cultural record mutually compatible operations: Pilot application at Kouklia-Palaepaphos ("Palaepaphos Pilot Project"). This three-year project (2007-2010) collaborated with the Institute for Mediterranean Studies of the Foundation of Research and Technology Hellas (IMS-FORTH) to develop a framework of principles for the management of archaeological landscapes to sustain modern development. The second project, entitled "The Palaepaphos Urban Landscape Project", is a long-term research and fieldwork programme, established in 2006. The project aims to investigate the development of the urban structure at Palaepaphos from the time of its foundation, to the end of Antiquity.The excavations of the University of Cyprus in the area of Palaepaphos concentrated on targeted areas, aiming to increase the exposure of the visible monuments and the polity's urban structure. The fieldwork expeditions conducted by the University of Cyprus have so far investigated five different localities within the Kouklia nucleus: Marcello (2006-2008), Hadjiabdullah (2009-2010, 2013-present), Arkallon (2010), Mantissa (2012) and Laona (2012-present).

|

|

PALAEPAPHOS (OLD PAPHOS): CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

|

|

THE FOUNDATION HORIZON

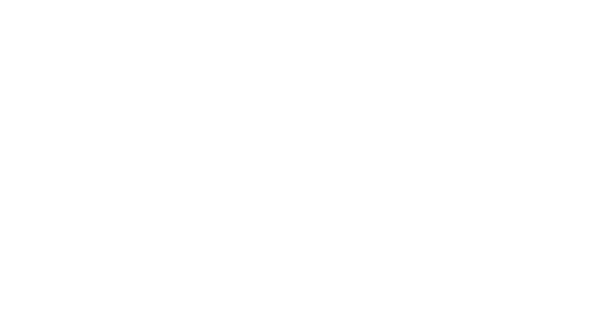

Palaepaphos was founded at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, at around 1600 BC. It was during this period of time that Cyprus acquired its first port-settlements, for example Enkomi, Kition and Hala Sultan Tekke.These sites were established as ports for the export of copper, the main export commodity of the island during the Late Bronze and the Iron Age eras.

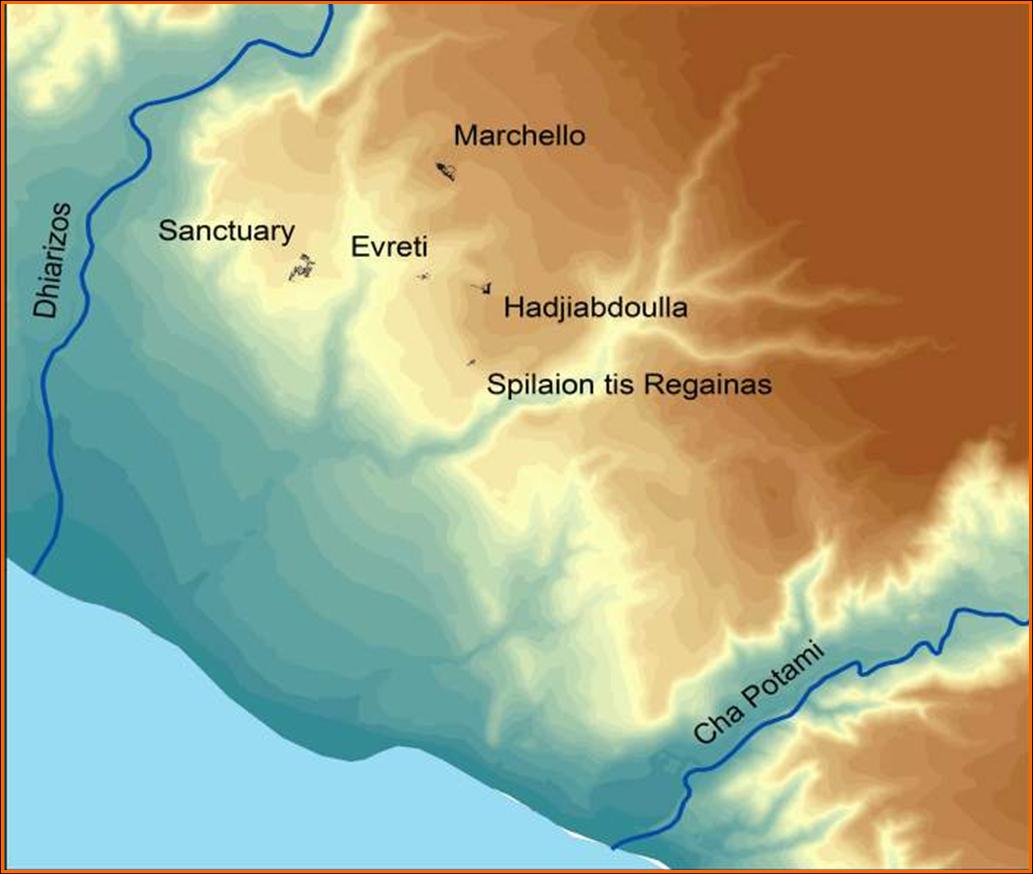

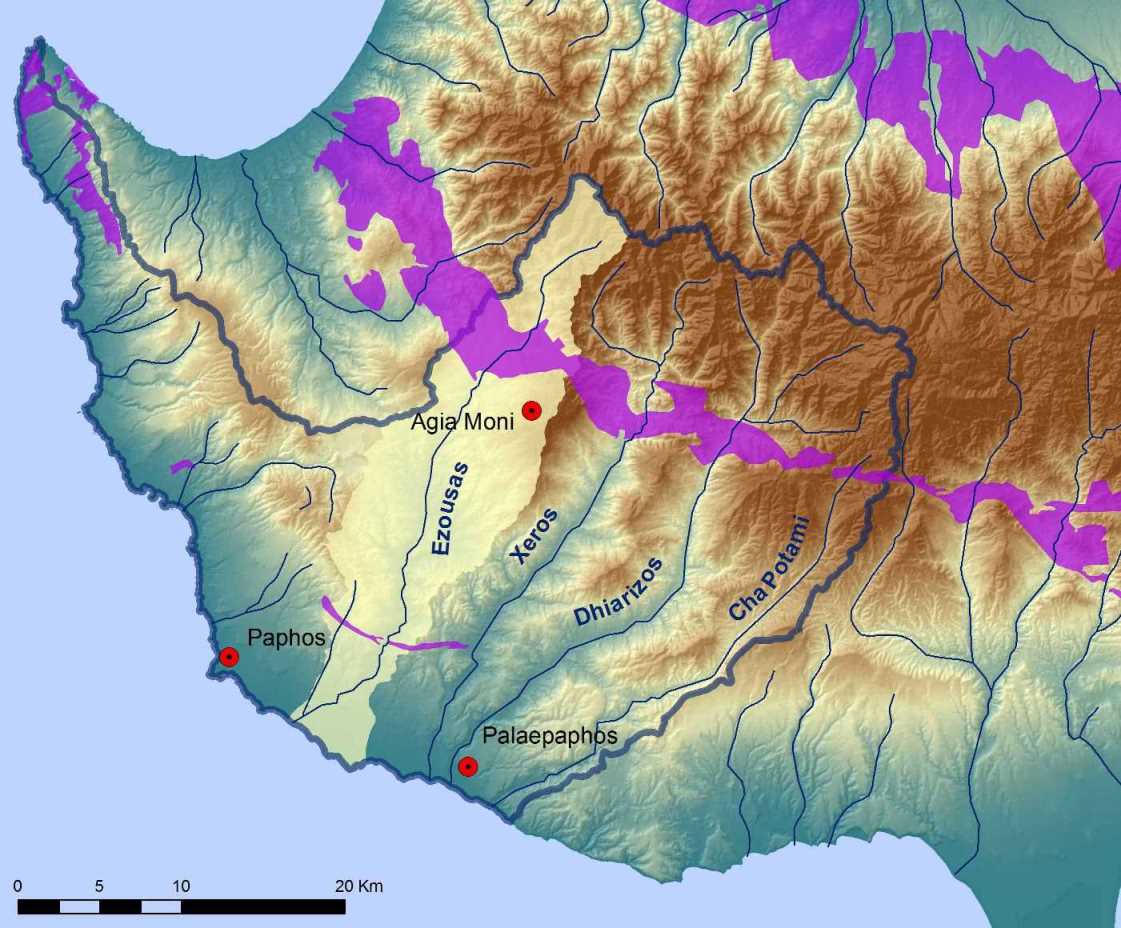

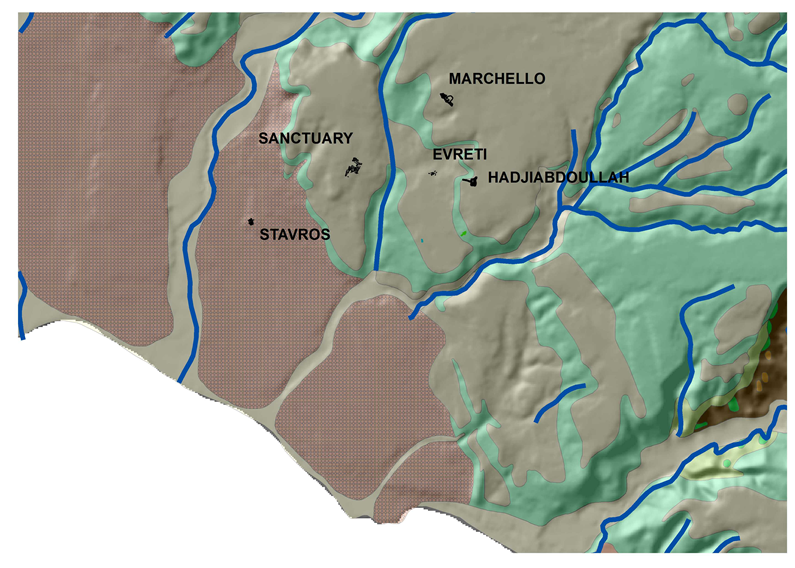

These processes are traced by an increase in the number of sites within the Paphos catchment area during the Middle Cypriot III-Late Cypriot IA period. During this phase, Palaepaphos was the terminal link in a chain of settlements that were involved in the extraction, transportation and overseas export of copper. The subsequent Late Cypriot IB period was marked by a substantial decrease in the number of sites, whereas the evidence from the coastal settlement at Kouklia became much more substantial. The foundation of Palaepaphos is related to the island-wide processes that replaced the village-based agricultural economy of Early and Middle Bronze Age with a new economy which relied heavily on the export of copper. At the time of its foundation, Palaepaphos acted as the regional gateway centre of the Dhiarizos valley, linking a chain of settlements that extended from the metalliferous zones of the Troodos foothills to the coast and by extension to long-distance trade.

|

|

| |

|

THE LATE BRONZE AGE

By the 13th century BC, this port-settlement became the economic and political centre for the entire Paphos region. Late Cypriot chamber tombs and their settlements are located in clusters to the North and East of the village of Kouklia, at the localities of Evreti, Asproyi, Marchello and Kaminia. The wealth of the tombs attests to the high prominence of Paleapaphos in the site hierarchy of the Paphos area. The co-existence of mortuary and secular material at the localities of Asproyi, Evreti and Teratsoudhia suggests that Palaepaphos followed the Late Cypriot mortuary custom of establishing tombs within residential areas, similar to the case of Enkomi and other Late Bronze Age sites.

At the locality of Evreti, the two well-shafts TE III and TE VIII were found filled with large numbers of storage and fine-ware vessels, animal bones, ivory waste, faience fragments, bronzes and various small household objects. The wells represent residential and industrial activities of the area, possibly in relation to ivory carving and possibly also metalworking. Another well discovered at Teratsoudhia contained pottery, bronze, lead, faience and ivory artefacts, dating from the Late Cypriot I to the Late Cypriot IIIA period.

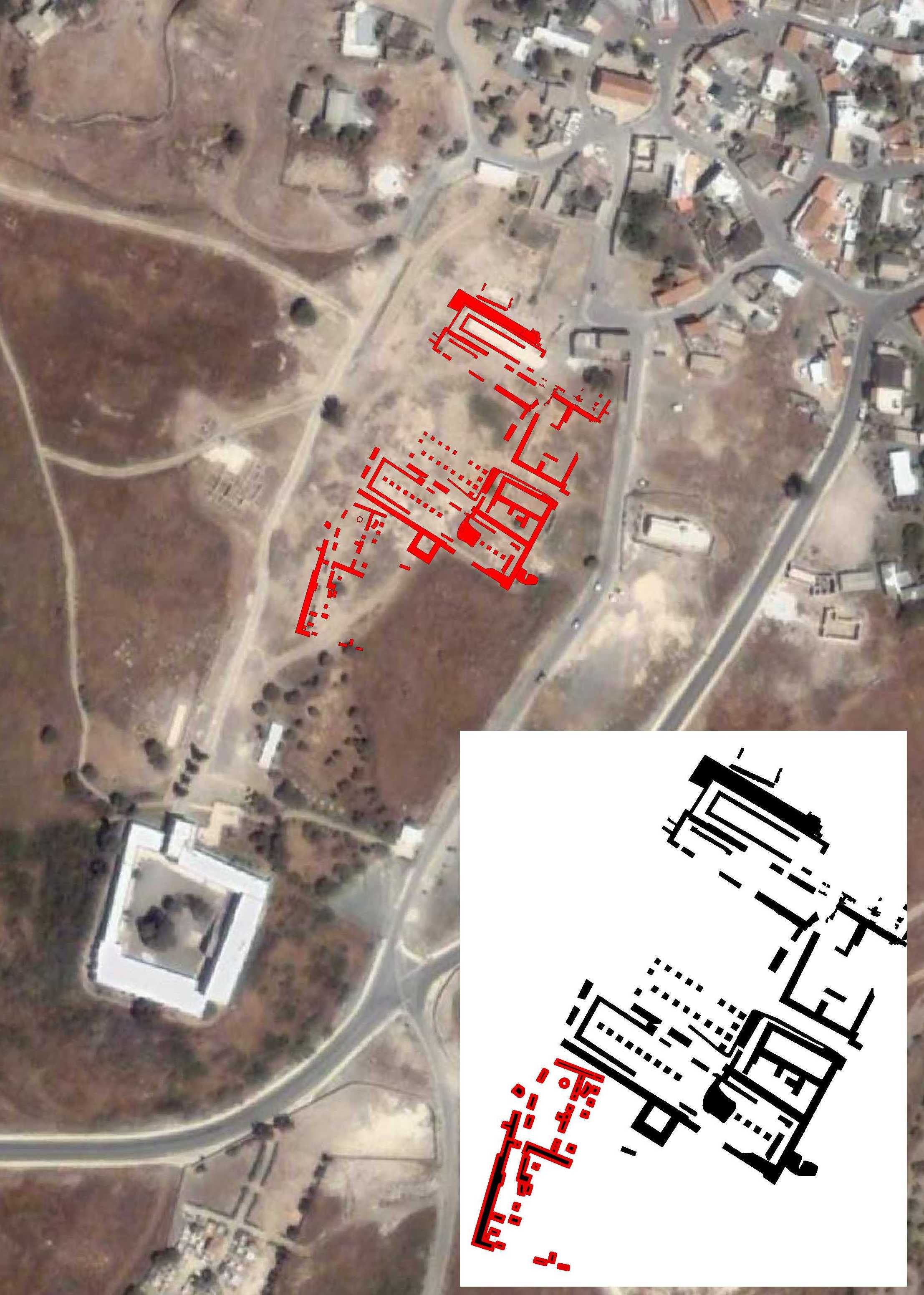

The prosperity of the polity is epitomized by the construction of a monumental sacred temenos early in the 12th century BC, where the Cypriot Goddess (the Kypris) was worshipped. This megalithic Sanctuary continued to function as a place of adoration for a female deity down to the Roman era. In historic times, the deity became known as Aphrodite.

The establishment of the megalithic temenos was accomplished in the course of the "Crisis Years". This term describes the collapse of the Late Bronze Age empires and palace states. The blow for some of the Cypriot polities was serious. Apparently, the reduced demand for Cypriot copper abroad caused a production breakdown. This is identified in a horizon of settlement abandonments.

|

|

|

Palaepaphos seems to have profited from this. The transition from the LCIIC to LCIIIA heralded an era of territorial expansion and urban nucleation. During this unsettling period, Palaepaphos evidently managed to concentrate so much strength – translated as agricultural and industrial territories as well as man-power – that she could afford to give monumental expression to her communal cult centre. The construction of the megalithic sanctuary must have been planned and executed by a centralized political authority. The Sanctuary at Palaepaphos preserves the most substantial Late Bronze Age architectural evidence for this polity, despite its extensive remodeling during Roman times. Owing to its bad state of preservation, the ground-plan and elevation of the Late Bronze Age sanctuary at Palaepaphos has been variously reconstructed. Its preserved excavated remains consist of two contiguous rectangular units. The southern unit was designated as an open courtyard or a temenos. It is enclosed by a substantial wall in the west, built of megalithic dressed limestone orthostats, reaching up to 5m in length and 2.2m in height, raised on a pediment of rectangular blocks.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE EARLY IRON AGE

The Early Iron Age encompasses the Late Cypriot IIIB, the final phase of the Late Bronze Age in Cyprus (c. 1125-1050 BC) and the Cypro-Geometric period (c. 1050-750 BC). The beginning of the Early Iron Age is distinguished by the introduction in Cyprus of a new type of grave, the chamber tomb with a dromos that originated in the Aegean. Its introduction to Cyprus and its island-wide use from the 11th century onward marked the replacement of the standard (since Early Cypriot) Bronze Age grave on Cyprus.

Palaepaphos is ringed by incredibly rich burial grounds of the Cypro-Geometric period. The tombs contain an amazing collection of vessels, weapons and tripods in bronze as well as spits (obeloi) and knives of iron. The content of these cemeteries is extremely valuable evidence of local crafts and access to luxury goods.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

THE ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL PERIODS

Paphos, the name by which the Archaic and Classical period polity is identified, is first attested in the 7th century BC on the prism of Esarhaddon (673/2 BC). The long cuneiform text on this Neo-Assyrian royal inscription contains a unique list with the names of ten Cypriot leaders and their respective seats of authority. The Greek-named Ituander (Etewandros) is identified as 'sharru' (king) of 'Pappa' (Paphos).

From the later 7th to the end of the 4th century BC inscriptions in the Cypriot syllabary also identify the polity as Paphos and its succession of leaders as basileis. The earliest Greek inscriptions, written in the island's Cypriot syllabary, which introduce the term pa-si-le-wo-se are inscribed on a silver plate and on a pair of solid gold bracelets. The plate, dated circa 725-675 BC, is claimed as property of Akestor, basileus of Paphos. The bracelets belonged to Etewandros, also basileus of Paphos.

The Neoassyrian kings were the masters of an intricate Mediterranean market economy under which the kingdoms of Cyprus thrived. By the end of the 6th century the Neoassyrian Empire began to decay. The Cypriot kings decided to declare their allegiance to whom they had foreseen as the upcoming power of the region, the Persian King. From the end of the 6th until the appearance of Alexander the Great on the scene, the Cypriot kingdoms were integrated in the Persian Empire. However, they retained their autonomy as is evidenced by the minting of coins that conform to a Cypriot weight standard and depict symbols of the power of the indigenous kings. A complete Greek syllabic inscription which was found at Marchello is one of the earliest royal lapidary inscriptions of Paphos and it provides us with the names of at least two Paphian kings, Onasicharis and his father, Stasis."Of Onasicharis king of Paphos, son of Stasis king of Paphos, son of Stasiphilos". The inscription was found in a huge bothros that abuts the wall of Marchello, along with material supposed to have come from an elusive sanctuary site. The material comprises the largest corpus of royal inscriptions and royal statuary ever to have been found on Cyprus.

|

|

|

Herodotus informs us that some of the Cypriot city kingdoms raised a struggle against the Persians just after the Ionian Revolt in 499. According to the Greek historian, the struggle was unsuccessful and soon afterwards the Persians re-conquered the rebel cities. Herodotus never explicitly mentions Paphos in his Historiai, however, Mitford and Iliffe proposed that the bothros at Marchello was created by the Persians who destroyed a sanctuary and used the material in order to erect a siege mound and enter the city of Paphos. Another nine lapidary inscriptions and a number of coin legends, all in Greek syllabic, provide the names of the Paphian kings of the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Of all the kings of Cyprus who are epigraphically recorded, only the Paphian kings who reigned in the Cypro-Classical period insisted on introducing themselves as basileis of Paphos and iereis of the wanassa.

|

|

Nikokles, the last king of Paphos

Nikokles, the son of king Timarchos, was the last king of Paphos. He reigned at the time of Alexander and he was one of the Cypriot kings who assisted the Macedonian fleet to conquer Tyre. Nikokles appears in no less than five syllabic inscriptions. He is also responsible for the issue of a digraphic inscription: the Greek text is recorded both in the native syllabary and in the alphabet.

Nikokles is most probably the Paphian king mentioned in an inscription found at the sanctuary of Hera at Samos. According to Diodorus, Nikokles was violently assassinated along with other members of the royal family by Ptolemy Soter in 312, as he was suspected to have formed an allegiance with his rival, Antigonus. After this tragic event, his wife Axiothea convinced the women of the family to commit suicide. Thus the Greek historian describes the violent termination of the royal house of Paphos, the Kinyradhai.

We believe that before his tragic death, Nikokles relocated his administrative capital 11 km to the west, in search for better port facilities. Thus, he laid the foundations of a new harbour, Nea Paphos, which shortly afterwards became the administrative capital of Ptolemaic and later Roman Cyprus. Two of the syllabic inscriptions of Nikokles come from the site of Ayia Moni, at the southwestern foothills of Troodos.

To this day no other royal inscription has ever been found at such a remote distance from its political centre. These two royal inscriptions, with which Nikokles commemorates the establishment of a temenos to Hera in the remote highlands of Ayia Moni, show the king's concern and probably advanced planning as to the new route that was to carry copper from the Troodos metalliferous regions to the harbour of Nea Paphos.

|

|

|

|

|

|

HELLENISTIC AND ROMAN PERIODS

Palaepaphos appears to have lost its prominent role as capital centre of the kingdom of Paphos towards the end of the 4th century BC, when it could no longer serve as commercial harbour. When a new harbour was established 11 kilometres to the west the administrative centre of the Paphian region was also transferred close to the new port facilities, namely at Nea Paphos. The transfer of the capital city to Nea Paphos should be credited to its last king Nicocles, though some scholars would argue that this was done by Ptolemy I.

The urban landscape of Palaepaphos began to shrink as secular units of the kingdom's old capital were being abandoned. During the Hellenistic and Roman period only the sanctuary continued to receive attention, and, its direct environs were heavily remodelled to accommodate the needs of pilgrims. It became the island's most important sacred place, since it was connected with the cult of the new rulers.

However, no other public buildings (such as gymnasia, theatres and baths) were erected, as was the case for example with Kourion, Amathous and Salamis, since the site had no administrative significance. And thus, ancient Paphos was transformed from an urban centre to a sanctuary site. It was then that it ceased to be called Paphos and it started to be referred to as Palaea (Old) Paphos.

|

|

|

|

|

|

LATE ANTIQUITY AND MEDIEVAL PERIOD

With the advent of Christianity, Palaepaphos also lost its religious significance. Since in Late Antiquity it was not a populous harbour town, no early Christian basilicas were constructed near or on top of its "pagan" cult centre.

By the Frankish period, Old Paphos had become an agricultural community within the feudal estate of the royal family of the Lusignans. Under the Lusignan dynasty (1192-1489) Cyprus became an important centre of cane-sugar production, and a large part of the royal domains were situated in the coastal plain of western Cyprus. The Château de Couvoucle, with its dependent industrial buildings on the Sanctuary site and in the locality Stavros was erected by the Lusignan kings of Cyprus in the 13th century. It served as a centre of local administration and as the headquarters of the royal official who directed and controlled the profitable sugar-cane plantations and refineries in the Paphos area.

After the end of Frankish rule the Lusignan Royal Manor House served as the centre of administration for the Kouklia chiftlik. The agricultural character of the community, known since as Kouklia, was retained virtually unchanged throughout the Venetian, Ottoman and British rule.

|

|

| |

|

|

|